Adaptation is Water

So Why is Water Still at the Margins of Climate Adaptation and Resilience Planning & Investment?

Note to Audacious Water subscribers: I’ve moved this newsletter to Substack. The platform has so many amazing writers and continues to explode in popularity. I encourage you to explore the great content here and expect more frequent updates from me.

Also: Check out this other new content from me:

Forbes: It’s Fourth and Long for Coastal Resilience in New Orleans

My latest podcast episode—a conversation on New Orleans 20 years after Katrina, featuring Charles Allen of the National Audubon Society and the Lower 9th Ward Center for Sustainable Engagement and Development.

We tend to think of climate change in terms of temperature: heat waves, wildfires, melting glaciers. But if you want to understand how climate change is truly reshaping our world, follow the water.

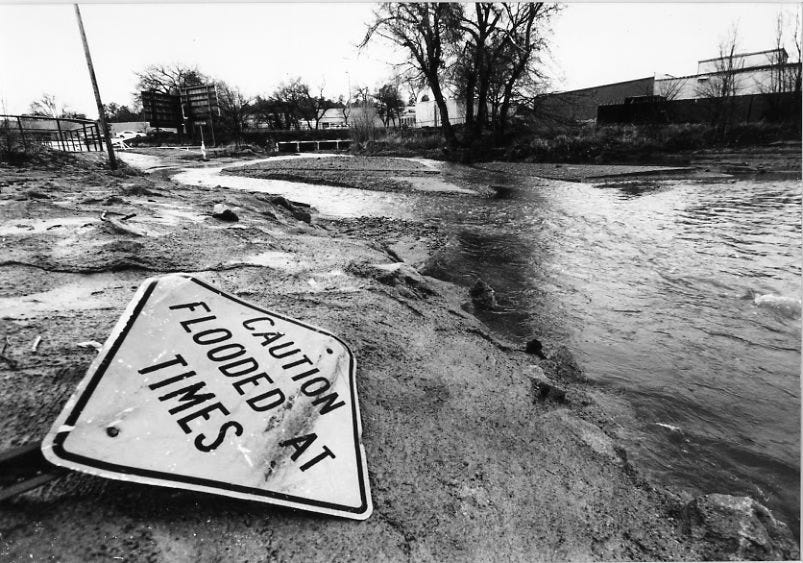

Droughts empty reservoirs and drive food insecurity. Floods destroy homes and bankrupt local economies. Coastal cities are drowning, while inland communities struggle with failing wells and depleted aquifers.

And yet, despite overwhelming evidence that climate change manifests through water, most adaptation plans in the U.S. treat water as just one challenge among many, rather than the central force that will define our future. This approach is not just misguided—it’s dangerous.

We must make water the organizing principle of climate adaptation, ensuring that resilience efforts protect not just people and infrastructure but the very water systems on which both depend.

That’s going to require not just a shift in priorities, policy and investment, but a shift in the way we think about nature itself.

Water as the Primary Climate Impact Driver

Climate change impacts are overwhelmingly expressed through water. Warming temperatures intensify the hydrologic cycle, leading to heavier rainfall, stronger droughts, and rising seas. In fact, over 90% of disasters are weather- and water-related—from floods and storms to droughts and wildfires. Recent studies confirm what the IPCC has long warned: Both the frequency and intensity of extreme wet and dry events have increased over the last 20 years globally. Heavier downpours are already causing more frequent inland flooding, while an accelerated water cycle means droughts last longer and hit harder—with consequences for agriculture, infrastructure, and drinking water supplies.

We must make water the organizing principle of climate adaptation...And that’s going to require not just a shift in priorities, policy and investment, but a shift in the way we think about nature itself.

Sea-level rise is another water-driven threat. Global average sea level has risen 8–9 inches since 1880, reaching record highs in 2023. The rise is accelerating, and another 10–12 inches is expected along U.S. coasts in just the next 30 years. Coastal flooding, erosion, and storm surge events are intensifying, putting millions at risk. Even far from coasts, water scarcity is growing: the United Nations estimates that 3.2 billion people now live in agricultural areas impacted by very high water shortages or water scarcity.

In short, whether it’s too much water or too little, climate change manifests primarily through water-related extremes. Any effective adaptation strategy must therefore confront water issues head-on.

Gaps in U.S. Adaptation Planning and Investment

Despite water being the medium through which climate impacts are felt, U.S. climate adaptation efforts have not yet fully prioritized water resilience. Adaptation initiatives remain fragmented across agencies—for example, FEMA handles flood response and levees, USDA addresses drought in agriculture, EPA funds drinking water and wastewater upgrades, and HUD focuses on resilient housing. Without a unifying water-centered plan, water can become an afterthought.

A consequence of this siloed approach is underinvestment in proactive water infrastructure upgrades. The American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) finds the U.S. faces a nearly $1 trillion water infrastructure investment gap over the next 20 years. Aging drinking water pipes, sewage systems, dams, and levees need massive overhaul to withstand climate stress, yet funding falls short. The federal government historically provides only a small fraction of water infrastructure funding (around 9%), leaving most costs to local governments. By comparison, sectors like transportation receive far higher federal support, highlighting a misalignment in priorities.

Recent steps have begun to address this—the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law delivered $50–55 billion for drinking water, wastewater, and stormwater systems, the largest federal infusion in decades. However, this is only a fraction of the over $630 billion that the EPA estimates is needed in the next 20 years just to maintain and replace U.S. water systems. In other words, current investments will cover well under 10% of the documented needs.

Moreover, many federal and state climate adaptation plans do not treat water management as a central organizing principle. For instance, climate resilience funding often targets projects like elevating homes or strengthening power grids, while critical water projects (levee improvements, wetland restoration, modern irrigation systems, etc.) compete for limited funds. Where water initiatives exist, they are frequently reactive—e.g., disaster relief after floods—rather than upfront resilience-building. This gap in planning and investment leaves communities vulnerable to the next flood or drought even as those threats accelerate.

Reimagining Resilience: Water-Centered Adaptation and the Economic Case for ‘New Nature’

To truly build climate resilience, water must move to the center of adaptation policy and investment. This first means integrating water considerations across all planning—treating floods, droughts, stormwater, groundwater, and water quality as interconnected challenges.

One promising example of such integration: Minnesota’s “One Watershed, One Plan” program, which replaces fragmented county-by-county water plans with comprehensive watershed-scale management plans.

But we need to move past our legacy bias about water-centered adaptation as just an ecological necessity. That’s because water-centered adaptation also makes strong economic sense: Natural infrastructure—like wetlands, floodplains, and green stormwater systems—often delivers equal or better performance at lower cost than traditional “gray” infrastructure.

When we plan for floods, droughts, and water management in an integrated way, we not only reduce climate risks but also create economic value.

And the right approach will transcend individual projects to embrace a new way of thinking about infrastructure itself. Instead of treating climate adaptation as a series of isolated engineering challenges, we must invest in New Nature—strategically engineered natural systems that store floodwaters, recharge aquifers, purify water, and create economic value.

The U.S. Midwest is the perfect place to lead this transformation. With its increasing flood risks, depleting groundwater, and aging infrastructure, the region is primed for a large-scale shift toward natural water solutions. Restored wetlands and floodplains along the Mississippi River, for instance, could reduce flood damage while creating new recreational economies. Agricultural states like Iowa and Nebraska could invest in aquifer recharge zones and precision irrigation, turning farms into water storage assets rather than just consumers. Cities from Chicago to St. Louis could replace aging stormwater pipes with green infrastructure that absorbs rainwater, beautifies urban spaces, and reduces heat islands.

These solutions aren’t just theoretical. The Milwaukee Metropolitan Sewerage District has already proven that green infrastructure can be cheaper and more effective than traditional sewers. New York City avoided a costly $8-10 billion filtration plant by instead investing $2.5 billion in watershed protection in the Catskills, ensuring natural filtration through forests and wetlands—saving billions in capital and operational costs. And wetlands can act as cost-free flood insurance: A Nature study found that U.S. wetlands prevented $625 million in damages during Hurricane Sandy alone.

Resilience Flows From Putting Water First

By recognizing water as the linchpin of climate impacts, policymakers can direct resources and ingenuity to where it matters most. A water-centered adaptation strategy—one that fortifies natural and built water systems against extremes—will pay off in safer communities, robust economies, and healthier ecosystems.

The science and case studies show that when we plan for floods, droughts, and water management in an integrated way, we not only reduce climate risks but also create economic value. It’s time to move water from the margins to the center of climate adaptation efforts.

Prioritizing water now will determine whether our communities thrive or thirst in the climate-challenged decades to come. Resilience flows from putting water first.